The First 100 Years by Ann Reichmann

Learn More About Taylor’s Mexican Chili Company

The year 2004 turned into a celebration time for many people in the Midwest. St. Louis topped the list by celebrating its great World’s Fair of 1904 – a fair boasting a gigantic roller coaster that tightened throats and tingled stomachs as the cars roared up, down and around steep bends. Carlinville, Illinois, has its own historic moment from the same year, and it also has a World’s Fair connection. During that same summer, Carlinville throats and stomachs tingled with their own new roller coaster ride, a gastronomic one, served in thick china bowls in a dusty little restaurant on the town’s Main Street. By name it was Taylor’s Mexican Chili. By reputation - it was hot! It still is.

Taylor’s Mexican Chili was a phenomenon waiting to happen. The history is simple. Carlinville native Charles O. Taylor, working at the Mexican National Exposition during the St. Louis World’s Fair, had his first taste of Mexican food. He tried the chili. He didn’t like it. He learned to make the tamales. They were better, especially because they soothed Taylor’s indigestion. Sensing an opportunity, Taylor turned entrepreneur. He scurried back to Carlinville, began making his own tamales and with the help of a two-wheel push cart, began selling the tamales, from saloon to saloon, all 25 of them. Needing an extra hand, Taylor forked out three dollars to bail a Mexican vagrant out of jail, but demanded the vagrant work for him at 50 cents a week to pay off the fine. Taylor got an unexpected bonus. During that six-week period, the Mexican showed Taylor how to make chili con carne frijoles as his mother had made them in Mexico. Did Taylor like the chili? The answer seems obvious. He purchased the recipe from the Mexican and opened a tiny chili parlor at 218 West Main Street in Carlinville. It wasn’t a big spot in the road, but in no time it was filled with hungry customers.

So, isn’t chili just chili? Not according to those in this central Illinois town and county who have been gulping down the Taylor recipe for 100 years. Charles O. started with the usual ingredient - red beans, beans that he hand-sorted, soaked and cooked each day. The secret, however, was the chili sauce, an orange-brown mixture of shredded beef, chili peppers, onion, garlic and oleo oils which are made from selected beef fat. Topping the beans with the sauce gave the chili a distinctive flavor with particular POW-er. Carlinville residents discovered quickly that eating a bowl of Taylor’s Chili could keep one’s inner furnace stoked for a day or so and run rivulets of sweat down any brow even when the thermometer read way below zero. In a way, eating a bowl of Taylor’s was like eating fire without the flame. Once it caught on, people of Carlinville and even the surrounding areas were hooked.

Taylor’s first parlor featured a counter with just six stools and one table. In the beginning, the chili was made in Taylor’s home and transported to the chili parlor in his two-wheeled push-cart, steaming up the air, winter or summer. Perhaps that sparse seating was responsible for the attitude quickly adopted by Charles O. and later by his sons and grandsons who eventually took over the business. That attitude? Sit down, eat up, get up, and get out. And don’t ask for ketchup! Some older people remembered that the simple request for ketchup could bring about your immediate dismissal from the parlor. The chili was what the chili was. It needed no help, thank you very much. A tin cup measure of oyster crackers, a glass of water, buttermilk or milk and the chili. That was the menu. Don’t ask for coffee that ruined the taste of the chili, according to C.O.

Right from the start, Taylor had his rules. Customers had their choice: follow the rules or leave. For starters, when you walked in, you had your money ready - a nickel for a small bowl, a dime for a big one. Taylor brought your crackers and chili; you gave him the money on the spot. If you didn’t, he picked up the food and took it away. Second, Taylor tolerated no loitering. Taylor’s Chili Parlor was a place to eat. It was not the place for idle talk, conducting business, lighting up an after-dinner smoke or flirting with a waitress. In fact, you couldn’t find a waitress. There was just C. O. making no effort to be affable, just trying to get the eaters in and get the eaters out in 15 minutes, if possible. Charles O. ran the place himself, until his son, Ed, began working at the parlor at the age of 10 and continued until being called to service in WWI. This was a man’s place, serving a man’s meal; filling a man’s stomach and sending a man back to his job at noon or back home to his bed at night. Wives and children were tolerated just but they got little more than a nod of the head and a "sit down here" from the owner. As one person put it, "The owner was as hot as the chili." But the customers must have liked it. They kept coming back by the generations.

C.O. Taylor kept long hours. Starting early in the morning when the cooking began, extending (before prohibition) to late in the evening when the taverns closed, his chili was simmering. Whether for a late morning zippy eye-opener, a spicy lunch or a hot and tangy night-cap, the food was waiting for those who had a dime to spend and 15 minutes, no more than that to eat.

By 1919, the war was over, and the chili parlor had become a local success, worthy of a bigger spot. That year, Taylor, with the help of Ed I, opened a new and larger parlor in a former blacksmith/carriage repair shop right along the Interurban tracks. That move lasted 63 years. The new parlor featured 36 seats including the counter. The same rules prevailed. As soon as you finished your last bite, it was time for you to leave. People were waiting for your seat either now or they would be at any minute. They might be locals -- or they might be passengers from the Interurban train whose station was just a block ahead. As the chili’s reputation grew, the noon north-bound train would stop in front of the parlor, passengers would detrain and walk right into Taylor’s, gulp down their chili in 10 minutes, sprint the block to the train waiting at the station, climb aboard and continue their ride to Springfield and Bloomington. Knowledgeable and hungry passengers on the south- bound train would hop off at the station, sprint down the block to Taylor’s, rush in, eat up, and swing aboard the moving train as it slowly pulled away from the station and headed south.

The Great Depression hit both cities and small towns equally hard, but in little Carlinville, one business survived and even expanded. Pocket change was hard to come by in those years. Polly Kufa recalls having a small tin bank as a young girl --one that was locked. Only the bank had the key. That was meant to encourage children to save their money but keep them from robbing their own bank for frivolous reasons. Taylor’s Chili wasn’t "frivolous" in the minds of Polly and her friends. She remembers urging money from her own bank by sliding a knife into the money slot and jiggling it and the bank until coins came sliding out. She didn’t want all the money-- just enough for a bowl of chili.

Meat was also hard to find in those bleak years but soups and stews went far to feed a hungry stomach. So C. O. Taylor and his family created and added their own butterbean soup and vegetable soup. Customers kept coming. Some, perhaps most, wanting nothing but the famous chili; some wanting "halfers"- half chili and half butterbean; others wanting "butterbean with" (the soup with two spoonfuls of the famous chili sauce). The soups added marketing value to the menu. The Friday non-meat-eaters always had a place to go for lunch or supper. In addition, the more gently seasoned vegetable soup took care of those palates that couldn’t handle the fire. Those three menu items are still the mainstay of Taylor’s

During the ‘30s decade, with Ed Sr. taking over the reins, the Taylors ventured into canning the chili and the vegetable soup. By then an alley behind the parlor had been enclosed and converted into a cooking and canning area. The long process involved hand-dipping the beans and the sauce, and operating a hand-crank sealer as well as a pressure cooker. When WWII exploded on the world scene, cans were in short supply and often available only to those who were sending food to servicemen overseas. The meat and can shortage touched the Taylor operation and general canning was suspended; however, they managed to send cans of chili to hometown boys around the world. In some cases, using their helmets as a pan over small twig fires, many a Carlinville soldier heated his precious can of Taylor’s Chili and gulped down a taste of home.

In 1946, C. O. Taylor died, and Edward Taylor II had returned from the war to work with his dad in the business. Canning started up again, and Taylor’s Chili remained a favorite eating spot for residents of and visitors to the Carlinville area. Outside of the addition of the butterbean and vegetable soups, and the flat crackers (since oyster crackers were impossible to get) little had changed. The food stayed true to its reputation; the rules stayed true to Charles O’s desires. The sons had learned their lessons well -- about attitude and about cautious frugality. Whoever went to eat at Taylor’s knew the business was eating not socializing, and paying their way before, not after, they ate. John Russell relates a story that illustrates the finer points of Taylor management. . Russell, who spent some years in the late ‘40s and early ‘50s as part of a comedy team, became acquainted with the comedian Buddy Hackett. Russell had treated Hackett to a can of Taylor’s Chili, and Hackett was so impressed that he called the Chili Parlor to order six cases of the gourmet treat. Hackett gave his order to Ed Sr. and said, "As soon as the chili arrives, I will write you a check and send it to you." "Oooooh, no, you won’t," said Ed I. You send me the check. I’ll get it cleared. Then I’ll send you the chili." So famous or not, Hackett paid his bill before he got his treat.

That little building on the Interurban tracks stayed as true to itself as the food that was served. "Fancy" was not a word that interested Charles O. Taylor in 1904; "fancy" was not the word that interested the later members of the Taylor Chili enterprise. If paint had ever covered the outside of the wooden one-story building, it had all been washed away by time. Only a smallish red and white sign hung over the door to identify the place. Push open the door and walk in and the inside walls were as plain as the outside ones. The bleached, unpainted wooden floor showed spots where slivers had poked up or threatened to. Steam from the simmering soups and chili covered the windows and the walls. The wooden counter top and the plain wooden tables boasted no colorful tablecloths or place mats. The stools and chairs boasted no padded seats. The parlor boasted one thing - terrific food and water or milk to wash it down. That was it. And still the people came.

The late ‘40s, the ‘50s, the ‘60s brought little changes to Taylor’s Chili Parlor except for an increase of customers, both at home and across the country and small increases of the price of a bowl of chili or soup. Blackburn College students had discovered the spot years earlier. Where else could you get such a tasty meal for such a tasty price? A bowl of chili at Taylor’s and a movie made a pretty decent date night for money-strapped college students. It could also be used as a prank on unsuspecting coeds who weren’t quite ready for the chili fire. One day in 1948, two town boys, students at Blackburn, urged a Chicago coed to have lunch with them at a "wonderful restaurant in town." Naively, she went. They ordered a small bowl of chili for her and big bowls for themselves. "You won’t believe how good this is," the boys told her. Two bites into her lunch, she knew she was in trouble. Her mouth was on fire; her throat was seared. She couldn’t get enough water. Even the tears rolling from her eyes didn’t help. "I can’t eat this!" she cried. They were delighted. They thought she was kidding. "We won’t take you back to school until you finish," they announced. She was trapped. Her afternoon class started at 1:30 and her teacher had a no-absence, no tardy policy. It was 1:15. She begged. They laughed. She yelled. They laughed harder. She cried. They slapped each other on the back. Finally, she dumped the chili upside down on the table and walked out. They spent the afternoon trying to convince Ed that they should be allowed back in. She spent the afternoon chewing ice and calming the burning, but the heat that turned her off, turned most people on.

Take Marie Reichmann, for example. Marie was a Taylor’s fan. She was a devoted member of the Emmanuel Southern Baptist Church, a block away and it’s hard to know what she enjoyed more, the fiery sermon from the pulpit or the fiery big bowl of chili which she could down without shedding a tear. The hotter the better. Marie was a cook beyond measure, but she was the first to admit that she couldn’t come close to making a chili as good and as torrid as Taylor’s. She also would tell you that no medicine was any better at clearing out the sinuses than a bowl of Taylor’s Chili. Why go to the doctor when you could have a bowl of chili? Sunday for Marie wasn’t Sunday without church, and church wasn’t church without a stop afterwards for a big bowl of the good stuff.

Mike Golden, who grew up in Carlinville, had an after school and weekend job at Taylor’s in 1963. It’s an experience he never forgot. At that point the cost of a bowl of chili was 35-45 cents. Mike started out at 75 cents an hour. In two weeks he had proven himself and was advanced to 90 cents an hour. Ed Senior was as tough with the rules as his father had been before him. Mike remembers working for hours at a long table in the back room, picking through 100 pound gunny sacks of beans, removing the rocks and pebbles that came along for the ride. He also remembers Ed’s admonition about cleaning the big stainless steel vats in which the beans and sauce were cooked. "Scrub every vat two times. When you think they are absolutely clean, scrub them again." He reminded them to "Wash your hands if you touch anything. And then wash them again." Mike also learned the art of cutting the sleeves of crackers in half and then, removing the first 4 or 5 crackers so they could be served as extras. "No point in giving them more than they need," was Ed’s slogan. Mike could clean the beans, sweep the floor, scrub the vats, clear the tables and serve the drinks, but he could not touch the stove or serve the chili. That was Ed’s job.

Another favorite Ed saying was, "This is a family place." When would-be customers, with beer bottle in hand, would venture in the back door from the tavern just behind the chili parlor, Ed would send them on their way without a bowl of chili. He "didn’t need trouble and he didn’t need drunks." Children were OK. He even had a high chair or two, but he expected parents to keep their children under control and quiet.

Did the rules at Taylor’s change over the years? Not much. John Russell recalls the time his son Pete decided to entertain his new father in-law with a visit to Taylor’s. When the chili arrived, the usual succulent pool of grease was floating on top. "Oh. My," said the father in law. "Look at that grease. I’ll have to send this back or order a different bowl of chili." "No. No," Pete said. "If you complain, I’ll be barred from this place for life." It was a legitimate fear. If one of the Mr. Taylors didn’t want you as a customer, he made that clear and you didn’t darken the door again.

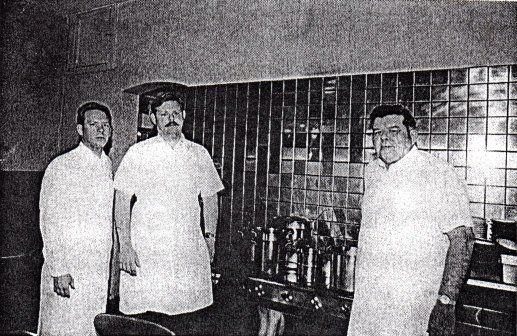

In 1957, both Ed Sr. and his brother-in-law died and Ed Jr. assumed control of the business. At that time Cynthia, Ed’s wife took over as bookkeeper and part-time worker. Ed’s son Tom, who had worked at the business as a boy, returned to it full-time in 1972. Ed’s other son; Ed III joined the business in 1973. Over all of those years the actual cooking of the chili was in the hands of only three people — Charles O., Ed Sr. and Ed Jr.

In 1982, Taylor’s Mexican Chili moved again; this time back to Main Street in the old Heinz Hotel building, renamed the Coach House Hotel. In order to attract a larger crowd in the day of new fast-food restaurants, the menu was expanded to include hot dogs, chili dogs and salads. Canning was discontinued because it was so time-consuming and not as profitable as they had hoped. However, the outlook for Taylor’s was grim and finally, the doors closed. "We had customers that stood in here and broke down and cried because they wouldn’t be coming here anymore," Ed Taylor related. "But we needed more volume. Volume is everything." Dave Card, Carlinville resident and fireman got the very last bowl of chili before the doors closed. He even took home the bowl as a memoir.

The family had hoped to restart the canning and get the product into stores here and nationwide, so that they would not be so dependent on Carlinville. That endeavor did not end successfully and the canning operation was abandoned.

In 1992, Taylor’s Chili had a new owner and a new location this time at The Glades Restaurant on the edge of Carlinville. People were excited that the chili was back, but none more excited than Dave Card who got the last bowl of chili when they went out of business and was first in line for the first bowl at the grand opening. Joe Gugger, native of Carlinville, had grown up on Taylor’s Chili and decided to purchase the name and the recipe and start all over again. That particular location was not conducive to the return of faithful chili customers. And the effort failed.

But it is alive and well today, in the summer of 2004. Owner Joe Gugger placed Dave Tucker at the helm, in-charge of cooking and canning Taylor’s Mexican Chili. The parlor is now located in the south half of the Anchor Inn on the square. Taylor’s customers, old and new, can again enjoy the heat and the flavor of the chili that has put Carlinville on the map. Oh, yes it’s on the map.

It even got into politics in a way. In 1976 President Gerald Ford was on a north-south Amtrak whistle stop tour through Illinois and scheduled to make a stop and a short speech in Carlinville. The train station was crowded with hundreds of Macoupin County people waiting for a glimpse of the president. Snipers stood atop the grain elevators across from the station, guns pointed towards the crowd, ready to stop any would-be assassins. Secret service agents had prowled the town for weeks. Many mingled inside the crowds that pushed and jostled to get near the President. Only a few people were allowed on the train platform from which Ford spoke. Among the proudest were the two captains from Carlinville High School’s conference, champion team who presented Ford with a football signed by the members of the squad. But, by far, the biggest cheers of the day came for those who gifted the president with Carlinville’s best-known home-town product, the familiar red and white can of the best chili in the world. The can had won security clearance by being x-rayed and then held in custody by the secret service. It was returned to those doing the presentation to the president just as they climbed onto the train platform.

Mike Golden, the former employee who now lives in the area of Rockford, Illinois, recalls customers who drove to Carlinville just for the chili. One couple from Jerseyville would drive over in their Thunderbird convertible most Sunday afternoons for their favorite treat - butterbean with chili and a shot of milk in the bowl. Golden, who has been involved in education all of his life, remembers being at workshops all over the state and being asked where he went to school. When he said, "Carlinville," many new acquaintances would say, "Oh! That’s the Taylor’s Chili town."

For years, cases of Taylor’s Chili have been sent as Christmas and birthday presents all over the United States and overseas. But perhaps the most telling evidence of the impact of this Mexican delight came just a few years ago. The story is told about a young Carlinville couple who had gone into Mexico on their honeymoon. When they were ready to return to the states, they could not find their identification papers. They went to the border to try to get through and were stopped. They explained to the border guard that they truly were American citizens who had been in Mexico on their honeymoon, but they had lost their identification papers. But please, would he let them back through the border. Finally, the guard said, "Where did you say you are from?" Their answer was, "Carlinville, Illinois." "Really," said the guard, "If you are from Carlinville, Illinois, what’s the name of the chili parlor in Carlinville?" "Taylor’s" was the reply. "Move on through" said the guard and the newly-weds were quickly across the border and back in the USA.

One hundred years is a long time for a product to stay on top without massive national advertising campaigns. Taylor’s Mexican Chili has stayed on top without the campaigns. All it took was word of mouth. The word was "GREAT!" You might want to try some.

Call Taylor’s Mexican Chili Company to get gourmet chili today!

217-854-8713